Dietary Factors

Some of the listed dietary factors (i.e., L-carnitine, coenzyme Q10, and lipoic acid) can be synthesized by the body.

L-Carnitine

Contents

Summary

- Our body produces L-carnitine from the essential amino acid lysine via a specific biosynthetic pathway. Healthy individuals, including strict vegetarians, generally synthesize enough L-carnitine to prevent deficiency. However, certain conditions like pregnancy may result in increased excretion of L-carnitine, potentially increasing the risk for deficiency. (More information)

- Because of its role in the transport of long-chain fatty acids from the cytosol to the mitochondrial matrix, L-carnitine is critical for mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. (More information)

- L-Carnitine supplementation is indicated for the treatment of primary systemic carnitine deficiency, which is caused by mutations in the gene that codes for the carnitine transporter, OCTN2. (More information)

- L-Carnitine is also approved for the treatment of carnitine deficiencies secondary to inherited diseases, such as propionyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency and medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, and in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. (More information)

- Evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that L-carnitine or acylcarnitine esters may be useful adjuncts to standard medical treatment in individuals with cardiovascular disease. (More information)

- Routine administration of L-carnitine to people with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis is not recommended unless it is to treat carnitine deficiency. (More information)

- Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) may help reduce the severity of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. High-quality evidence is needed to evaluate whether ALCAR may benefit the treatment of peripheral neuropathies associated with diabetes or caused by antiretroviral therapy. (More information)

- There is some low-quality evidence to suggest that supplemental L-carnitine or ALCAR may be beneficial as adjuncts to standard medical therapy of depression, Alzheimer's disease, and hepatic encephalopathy. (More information)

- There is little evidence that L-carnitine supplementation improves cancer-related fatigue, low fertility, or overall physical health. (More information)

- If you choose to take L-carnitine supplements, the Linus Pauling Institute recommends acetyl-L-carnitine at a daily dose of 0.5 to 1 g. Note that supplemental L-carnitine (doses, 0.6-7.0 g) is less efficiently absorbed compared to smaller amounts in food. (More information)

Introduction

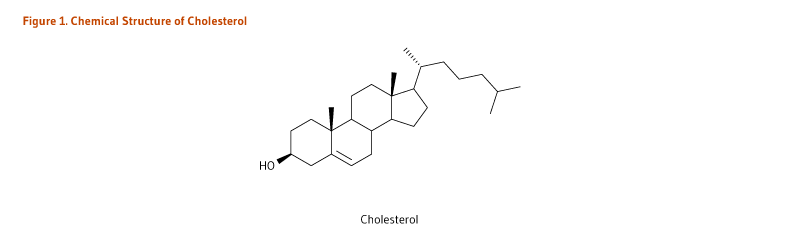

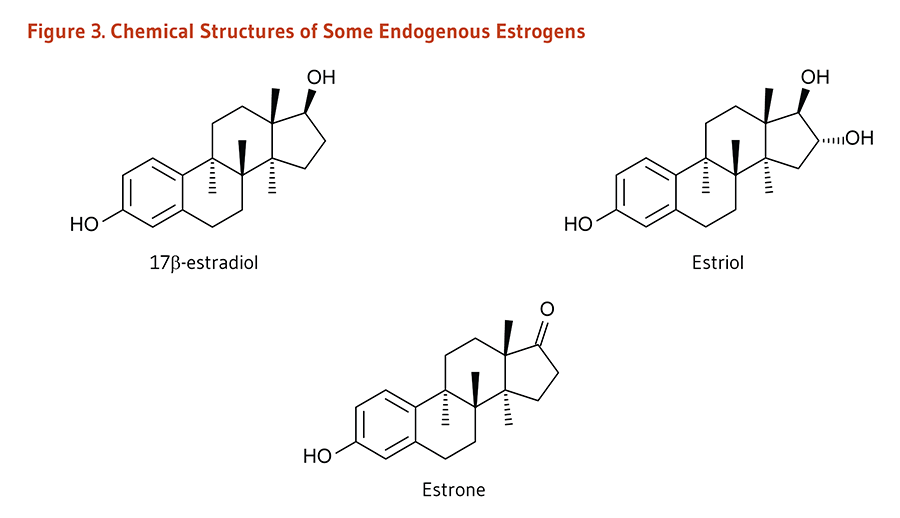

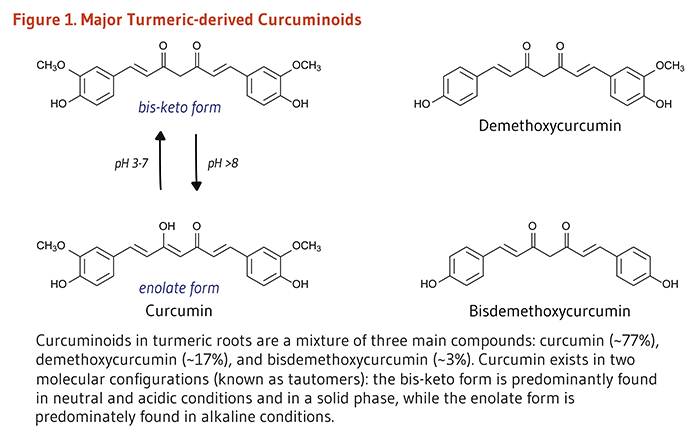

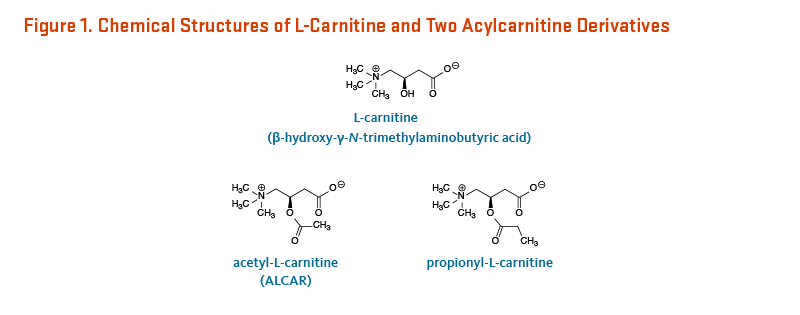

L-Carnitine (β-hydroxy-γ-N-trimethylaminobutyric acid) is a derivative of the amino acid, lysine (Figure 1). It was first isolated from meat (carnus in Latin) in 1905. Only the L-isomer of carnitine is biologically active (1). L-Carnitine appeared to act as a vitamin in the mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) and was therefore termed vitamin BT (2). Vitamin BT, however, is a misnomer because humans and other higher organisms can synthesize L-carnitine (see Metabolism and Bioavailability). Under certain conditions, the demand for L-carnitine may exceed an individual's capacity to synthesize it, making it a conditionally essential nutrient (3, 4).

Metabolism and Bioavailability

In healthy people, carnitine homeostasis is maintained through endogenous biosynthesis of L-carnitine, absorption of carnitine from dietary sources, and reabsorption of carnitine by the kidneys (5).

Endogenous biosynthesis

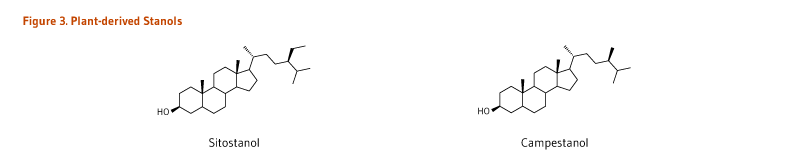

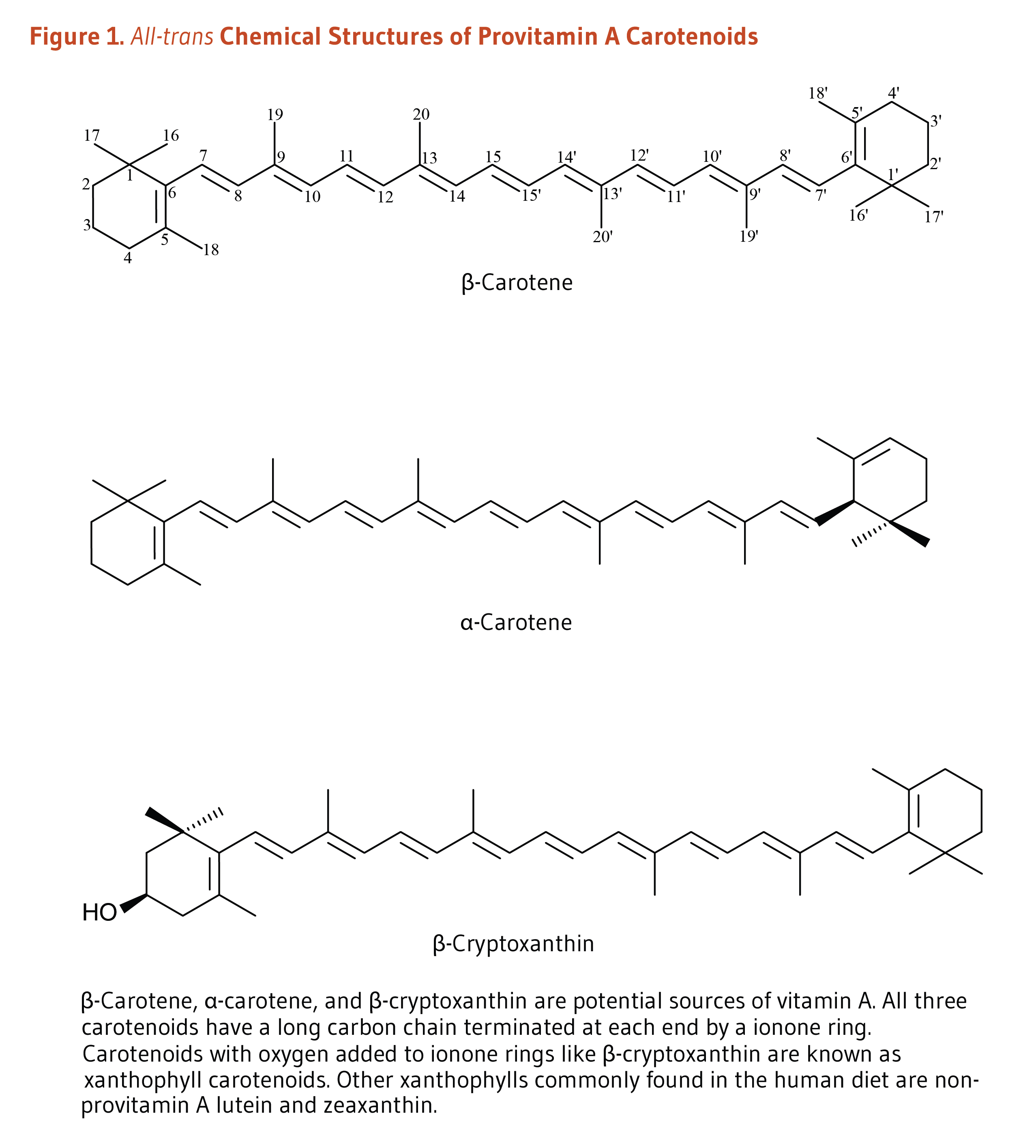

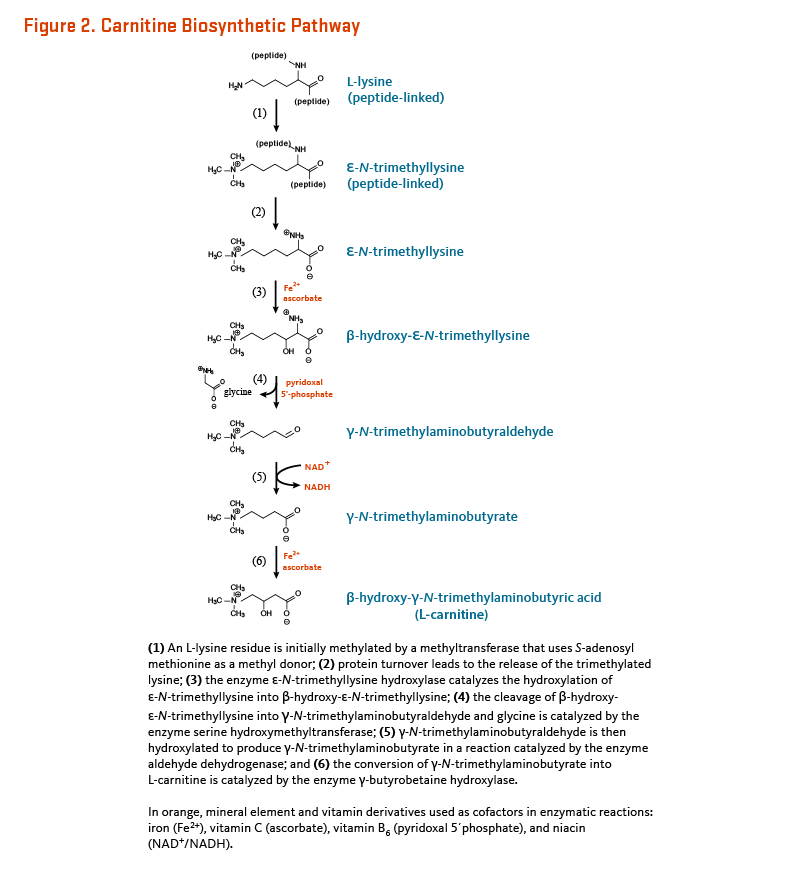

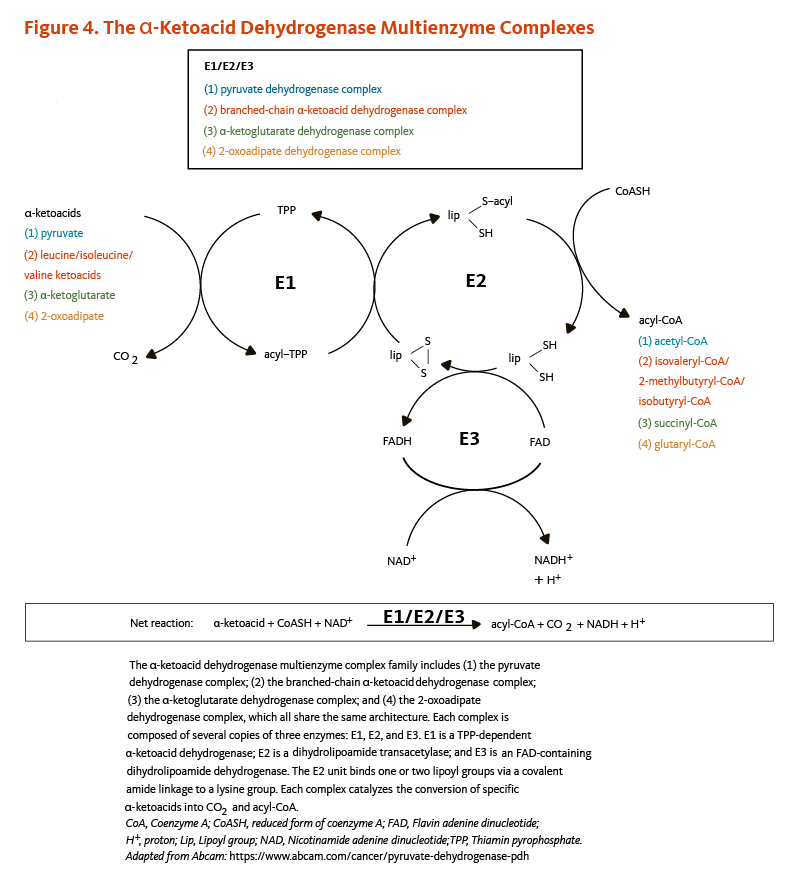

Humans can synthesize L-carnitine from the amino acids lysine and methionine in a multi-step process occurring across several cell compartments (cytosol, lysosomes, and mitochondria) (reviewed in 6). Across different organs, protein-bound lysine is methylated to form ε-N-trimethyllysine in a reaction catalyzed by specific lysine methyltransferases that use S-adenosyl-methionine (derived from methionine) as a methyl donor. ε-N-Trimethyllysine is released for carnitine synthesis by protein hydrolysis. Four enzymes are involved in endogenous L-carnitine biosynthesis (Figure 2). They are all ubiquitous except γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase is absent from cardiac and skeletal muscle. This enzyme is, however, highly expressed in human liver, testes, and kidney (7).

L-carnitine is primarily synthesized in the liver and transported via the bloodstream to cardiac and skeletal muscle, which rely on L-carnitine for fatty acid oxidation yet cannot synthesize it (8). The rate of L-carnitine biosynthesis in humans was studied in strict vegetarians (i.e., in people who consume very little dietary carnitine) and estimated to be 1.2 µmol/kg of body weight/day (9). The rate of L-carnitine synthesis depends on the extent to which peptide-linked lysines are methylated and the rate of protein turnover. There is some indirect evidence to suggest that excess lysine in the diet may increase endogenous L-carnitine synthesis; however, changes in dietary carnitine intake level or in renal reabsorption do not appear to affect the rate of endogenous L-carnitine synthesis (6).

Absorption of exogenous L-carnitine

Dietary L-carnitine

The bioavailability of L-carnitine from food can vary depending on dietary composition. For instance, one study reported that bioavailability of L-carnitine in individuals adapted to low-carnitine diets (i.e., vegetarians) was higher (66%-86%) than in those adapted to high-carnitine diets (i.e., regular red meat eaters; 54%-72%) (10). The remainder is degraded by colonic bacteria.

L-carnitine supplements

While bioavailability of L-carnitine from the diet is quite high (see Dietary L-carnitine), absorption from oral L-carnitine supplements is considerably lower. The bioavailability of L-carnitine from oral supplements (doses, 0.6 to 7 g) ranges between 5% and 25% of the total dose (5). Less is known regarding the metabolism of the acetylated form of L-carnitine, acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR); however, the bioavailability of ALCAR is thought to be higher than that of L-carnitine. The results of in vitro experiments suggested that ALCAR might be partially hydrolyzed upon intestinal absorption (11). In humans, administration of 2 g/day of ALCAR for 50 days increased plasma ALCAR concentrations by 43%, suggesting that either ALCAR was absorbed without prior hydrolysis or that L-carnitine was re-acetylated in the enterocytes (5).

Elimination and reabsorption

L-Carnitine and short-chain acylcarnitine derivatives (esters of L-carnitine; see Figure 1) are excreted by the kidneys. Renal reabsorption of free L-carnitine is normally very efficient; in fact, an estimated 95% is thought to be reabsorbed by the kidneys (1). Therefore, carnitine excretion by the kidney is usually very low. However, several conditions can decrease the efficiency of carnitine reabsorption and, correspondingly, increase carnitine excretion. Such conditions include high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets; high-protein diets; pregnancy; and certain disease states (see Primary systemic carnitine deficiency) (12). In addition, when circulating L-carnitine concentration increases, as in the case of oral supplementation, renal reabsorption of L-carnitine may become saturated, resulting in increased urinary excretion of L-carnitine (5). Dietary or supplemental L-carnitine that is not absorbed by enterocytes is degraded by colonic bacteria to form two principal products, trimethylamine and γ-butyrobetaine. γ-Butyrobetaine is eliminated in the feces; trimethylamine is efficiently absorbed and metabolized to trimethylamine-N-oxide, which is excreted in the urine (13).

Biological Activities

Mitochondrial oxidation of long-chain fatty acids

L-Carnitine is synthesized primarily in the liver but also in the kidneys and then transported to other tissues. It is most concentrated in tissues that use fatty acids as their primary fuel, such as skeletal and cardiac muscle. In this regard, L-carnitine plays an important role in energy production by conjugating to fatty acids for transport from the cytosol into the mitochondria (6).

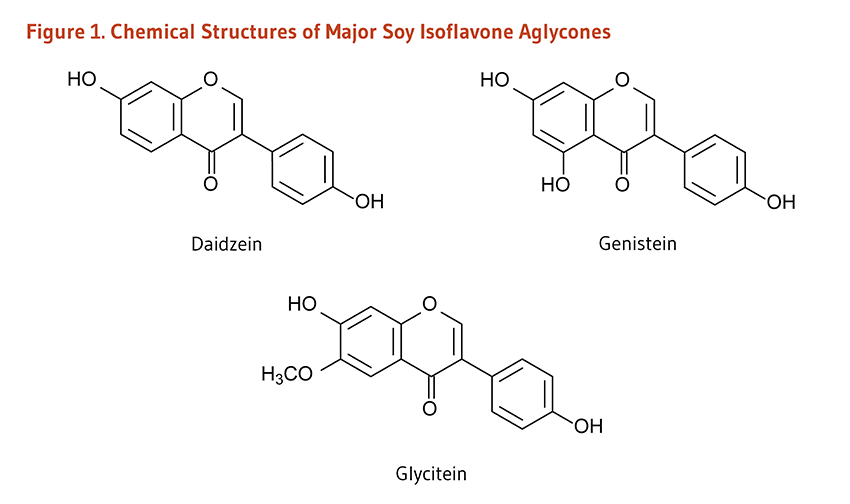

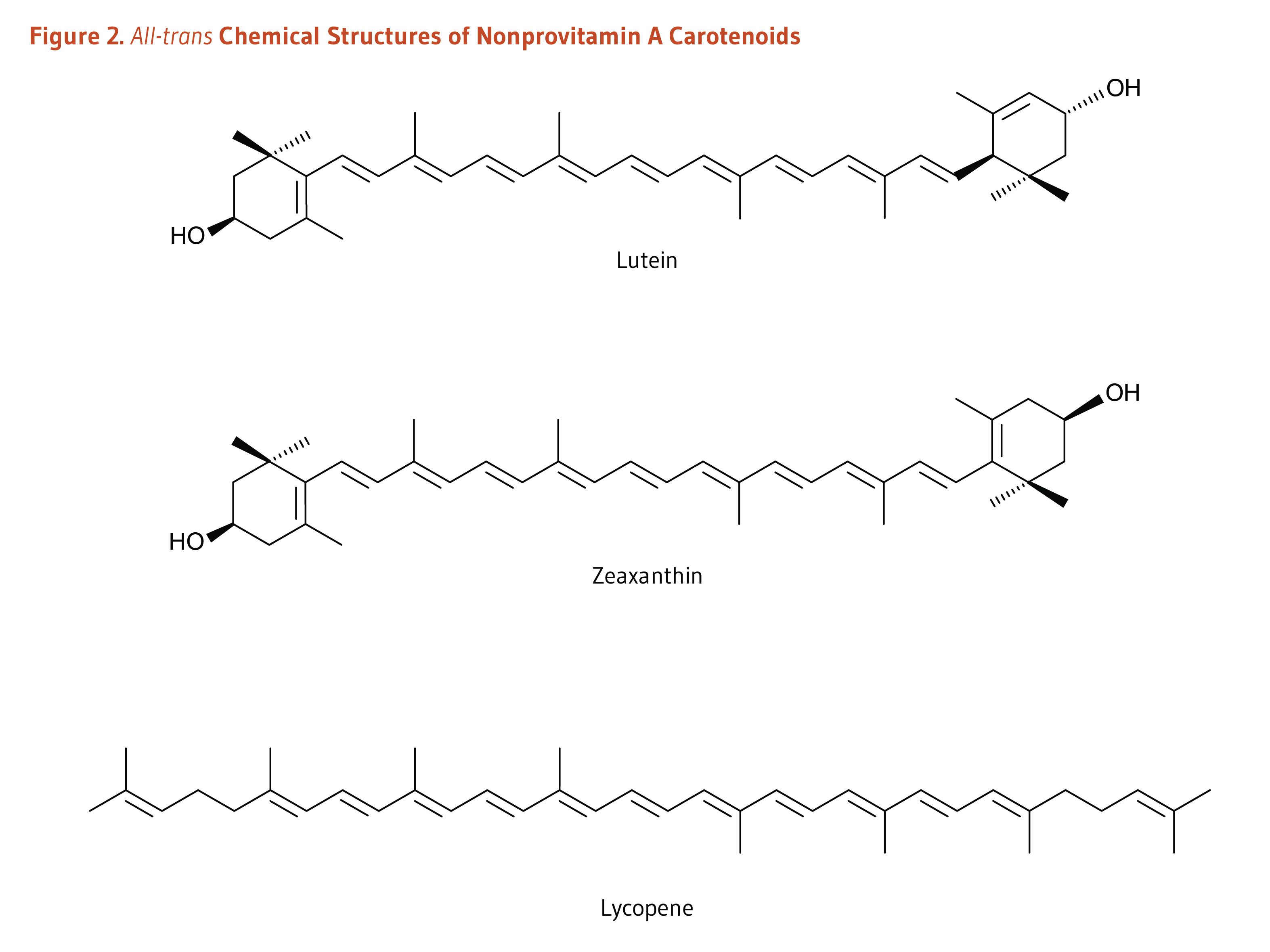

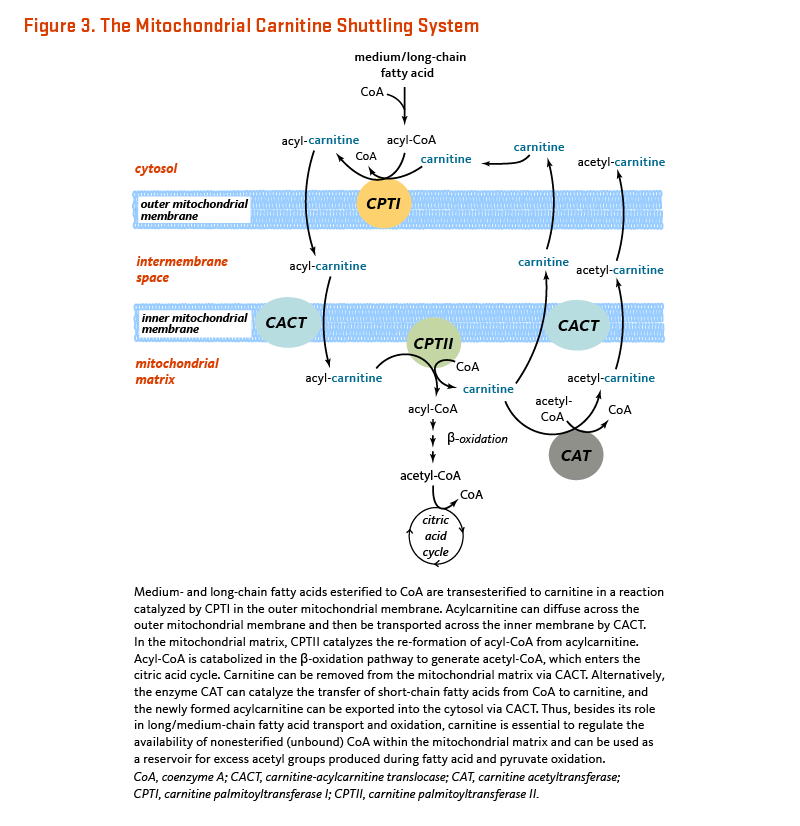

L-Carnitine is required for mitochondrial β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids for energy production (1). Long-chain fatty acids must be esterified to L-carnitine (acylcarnitine) in order to enter the mitochondrial matrix where β-oxidation occurs (Figure 3). On the outer mitochondrial membrane, CPTI (carnitine-palmitoyl transferase I) catalyzes the transfer of medium/long-chain fatty acids esterified to coenzyme A (CoA) to L-carnitine. This reaction is a rate-controlling step for the β-oxidation of fatty acid (13). A transport protein called CACT (carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase) facilitates the transport of acylcarnitine across the inner mitochondrial membrane. On the inner mitochondrial membrane, CPTII (carnitine-palmitoyl transferase II) catalyzes the transfer of fatty acids from L-carnitine to free CoA. Fatty acyl-CoA is then metabolized through β-oxidation in the mitochondrial matrix, ultimately yielding propionyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA (6). Carnitine is eventually recycled back to the cytosol (Figure 3).

Regulation of energy metabolism through modulation of acyl CoA:CoA ratio

Free (nonesterified) CoA is required as a cofactor for numerous cellular reactions. The flux through pathways that require nonesterified CoA, such as the oxidation of glucose, may be reduced if all the CoA available in a given cell compartment is esterified. Carnitine can increase the availability of nonesterified CoA for these other metabolic pathways (6). Within the mitochondrial matrix, CAT (carnitine acetyl transferase) catalyzes the transesterification of short- and medium-chain fatty acids from CoA to carnitine (Figure 3). The resulting acylcarnitine esters (e.g., acetylcarnitine) can remain in the mitochondrial matrix or be exported back into the cytosol via CACT. Free (nonesterified) CoA can then participate in other reactions, such as the generation of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate in a reaction catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase (14). Acetyl-CoA can then be oxidized to produce energy (ATP) in the citric acid cycle.

Other functions in cellular metabolism

In addition to its importance for energy production, L-carnitine was shown to display direct antioxidant properties in vitro (15). Age-related declines in mitochondrial function and increases in mitochondrial oxidant production are thought to be important contributors to the adverse effects of aging. Tissue L-carnitine concentrations have been found to decline with age in humans and animals (16). The expression of most proteins involved in the transport of carnitine (OCTN2) and the acylcarnitine shuttling system across the mitochondrial membrane (CPTIa, CPTII, and CAT; Figure 3) was also found to be much lower in the white blood cells of healthy older adults than of younger adults (17).

Preclinical studies in rodents showed that supplementation with high doses of acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR; Figure 1) reversed a number of age-related changes in liver mitochondrial function yet increased liver mitochondrial oxidant production (18). ALCAR supplementation in rats has also been found to improve or reverse age-related mitochondrial declines in skeletal and cardiac muscular function (19, 20). Co-supplementation of aged rats with L-carnitine and α-lipoic acid blunted age-related increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, and DNA strand breaks in a variety of tissues (heart, skeletal muscle, and brain) (21-30). Co-supplementation for three months improved both the number of total and intact mitochondria and mitochondrial ultrastructure of neurons in the hippocampus (30). Although ALCAR exerts antioxidant activities in rodents, it is not known whether taking high doses of ALCAR will have similar effects in humans.

Deficiency

Nutritional carnitine deficiencies have not been identified in healthy people without metabolic disorders, suggesting that most people can synthesize enough L-carnitine (1). Even strict vegetarians (vegans) show no signs of carnitine deficiency, despite the fact that most dietary carnitine is derived from animal sources (9). Infants, particularly premature infants, are born with low stores of L-carnitine, which could put them at risk of deficiency given their rapid rate of growth. One study reported that infants fed carnitine-free, soy-based formulas grew normally and showed no signs of a clinically relevant carnitine deficiency; however, some biochemical measures related to lipid metabolism differed significantly from infants fed the same formula supplemented with L-carnitine (31). Soy-based infant formulas are now fortified with the amount of L-carnitine normally found in human milk (32).

Carnitine status

Renal filtration maintains plasma concentrations of free carnitine around 40 to 50 micromoles (µmol)/L, while plasma concentrations of acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR; the most abundant carnitine ester) are around 3 to 6 µmol/L (8). Regardless of the etiology, plasma concentrations of free carnitine ≤20 µmol/L and increased acylcarnitine/free carnitine ratios (≥0.4) are considered abnormal (6). Low carnitine status is generally due to impaired mitochondrial energy metabolism or to carnitine not being efficiently reabsorbed by the kidneys. The rate of carnitine excretion is not a useful indicator of carnitine status because it can vary with dietary carnitine intake and other physiologic parameters. At present, there is no test that assesses functional carnitine deficiency in humans (6).

Primary systemic carnitine deficiency

Primary systemic carnitine deficiency is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations (including deletions) in the SLC22A5 gene coding for carnitine transporter protein OCTN2 (organic cation transporter novel 2) (33). Individuals with defective carnitine transport have poor intestinal absorption of dietary L-carnitine, impaired L-carnitine reabsorption by the kidneys (i.e., increased urinary loss of L-carnitine), and defective L-carnitine uptake by muscles (4). The clinical presentation can vary widely depending on the type of mutation affecting SLC22A5 and the phenotypic manifestation of the mutation, i.e., age of onset, organ involvement, and severity of symptoms at the time of diagnosis (34). The disorder usually presents in early childhood and is characterized by episodes of hypoketotic hypoglycemia (that can cause encephalopathy), hepatomegaly, elevated liver enzymes (transaminases), and hypoammonemia in infants; progressive cardiomyopathy, elevated creatine kinase, and skeletal myopathy in childhood; or fatigability in adulthood (34, 35). The metabolic and myopathic symptoms in infants and children can be fatal such that treatment should start promptly to prevent irreversible organ damage (34). The diagnosis is established by demonstrating abnormally low plasma free carnitine concentrations, reduced carnitine transport of fibroblasts from skin biopsy, and molecular analysis of the gene coding for OCTN2 (33, 34). Treatment consists of pharmacological doses of L-carnitine that are meant to maintain a normal blood carnitine concentration, thereby preventing the risk of hypoglycemia and correcting metabolic and myopathic manifestations (34).

Secondary carnitine deficiency or depletion

Secondary carnitine deficiency or depletion may result from either genetic or acquired conditions.

Hereditary causes include genetic defects in the metabolism of amino acids, cholesterol, and fatty acids, such as propionyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency (aka propionic acidemia) and medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (36). Such inherited disorders lead to a buildup of organic acids, which are subsequently removed from the body via urinary excretion of acylcarnitine esters. Increased urinary losses of carnitine can lead to the systemic depletion of carnitine (6).

Systemic carnitine depletion can also occur in disorders of impaired renal reabsorption. For instance, Fanconi's syndrome is a hereditary or acquired condition in which the proximal tubular reabsorption function of the kidneys is impaired (37). This malfunction consequently results in increased urinary losses of carnitine. Patients with renal disease who undergo hemodialysis are at risk for secondary carnitine deficiency because hemodialysis removes carnitine from the blood (see End-stage renal disease) (38).

One example of an exclusively acquired carnitine deficiency involves chronic use of pivalate-conjugated antibiotics. Pivalate is a branched-chain fatty acid anion that is metabolized to form an acyl-CoA ester, which is transesterified to carnitine and subsequently excreted in the urine as pivaloyl carnitine. Urinary losses of carnitine via this route can be 10-fold greater than the sum of daily carnitine intake and biosynthesis and lead to systemic carnitine depletion (see Drug interactions) (39).

Finally, a number of inherited mutations in genes involved in carnitine shuttling and fatty acid oxidation pathways do not systematically result in carnitine depletion (such that carnitine supplementation may not help mitigate the symptoms) but lead to abnormal profiles of acylcarnitine esters in blood (35, 40).

Nutrient interactions

Endogenous biosynthesis of L-carnitine is catalyzed by the concerted action of four different enzymes (see Metabolism and Bioavailability) (Figure 2). This process requires two essential amino acids (lysine and methionine), iron (Fe2+), vitamin B6 in the form of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate, niacin in the form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), and may also require vitamin C (ascorbate) (4). One of the earliest symptoms of vitamin C deficiency is fatigue, thought to be related to decreased synthesis of L-carnitine (41).

Disease Treatment

In most studies discussed below, it is important to note that treatment with L-carnitine or acyl-L-carnitine esters (i.e., acetyl-L-carnitine [ALCAR], propionyl-L-carnitine; Figure 1) was generally used as an adjunct to standard medical therapy, not in place of it. It is also important to consider the fact that the bioavailability of L-carnitine and acylcarnitine derivatives administered orally is low (~10-20%) (see Metabolism and Bioavailability). Intravenous administration is more likely to increase plasma carnitine concentration, yet homeostatic mechanisms tightly control blood concentration through metabolism and renal excretion: Up to 90% of 2 g of L-carnitine administered intravenously is excreted into the urine within 12 to 24 hours. Only a fraction of the dose is thought to enter the endogenous carnitine pool — largely found in skeletal muscle (reviewed in 8).

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Several small clinical trials have explored whether supplemental L-carnitine could improve glucose tolerance in people with impaired glucose metabolism. A potential benefit of L-carnitine in these patients is based on the fact that it can (i) increase the oxidation of long-chain fatty acids which accumulation may contribute to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, and (ii) enhance glucose utilization by reducing acyl-CoA concentration within the mitochondrial matrix (see Biological Activities) (42). A meta-analysis of five trials in participants with either impaired fasting glucose, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis found evidence of an improvement in insulin resistance with supplemental L-carnitine compared to placebo (43). Another meta-analysis of four randomized, placebo-controlled trials found evidence of a reduction in fasting plasma glucose concentration and no improvement of glycated hemoglobin concentration in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus supplemented with acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) (44). A third meta-analysis of 16 trials suggested that supplementation with (acyl)-L-carnitine may reduce fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin concentrations, but not resistance to insulin (45). In a recent double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the effect of ALCAR was examined in 229 participants treated for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (46). ALCAR supplementation (1 g/day for 6 months) had no effect on systolic or diastolic blood pressure, markers of kidney function (i.e., glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria), markers of glucose homeostasis (i.e., glucose disposal rate, glycated hemoglobin concentration, and a measure of insulin resistance), and blood lipid profile (i.e., concentrations of triglycerides, lipoprotein (a), LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and total cholesterol) (46).

Cardiovascular disease

In the studies discussed below it is important to note that treatment with L-carnitine or propionyl-L-carnitine was used as an adjunct (in addition) to appropriate medical therapy, not in place of it.

Myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction (MI) occurs when an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery ruptures and obstructs the blood supply to the heart muscle, causing injury or damage to the heart (see the page on Heart Attack). Several clinical trials have explored whether L-carnitine administration immediately after MI diagnosis could reduce injury to heart muscle resulting from ischemia and improve clinical outcomes. An early trial in 160 men and women diagnosed with a recent MI showed that oral L-carnitine (4 g/day) in addition to standard pharmacological treatment for one year significantly reduced mortality and the occurrence of angina attacks compared to the control (47). In another controlled trial in 96 patients, treatment with intravenous L-carnitine (5 g bolus followed by 10 g/day for three days) following a MI resulted in lower concentrations of creatine kinase-MB and troponin-I, two markers of cardiac injury (48). However, not all clinical trials have found L-carnitine supplementation to be beneficial after MI. For example, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 60 participants diagnosed with an acute MI, neither mortality nor echocardiographic measures of cardiac function differed between patients treated with intravenous L-carnitine (6 g/day) for seven days followed by oral L-carnitine (3 g/day) for three months and those given a placebo (49). Another randomized placebo-controlled trial in 2,330 patients with acute MI, L-carnitine therapy (9 g/day intravenously for five days, then 4 g/day orally for six months) did not affect the risk of heart failure and death six months after MI (50).

A 2013 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that L-carnitine therapy in patients who experienced an MI reduced the risks of all-cause mortality (-27%; 11 trials; 3,579 participants), ventricular arrhythmias (-65%; five trials; 229 participants), and angina attacks (-40%; 2 trials; 261 participants), but had no effect on the risks of having a subsequent myocardial infarction or developing heart failure (51). Because about 90% of oral L-carnitine supplements is unlikely to be absorbed, one could ask whether the efficacy is equivalent between protocols using both intravenous and oral administration and those using oral administration only (8). This has not been examined in subgroup analyses.

Heart failure

Heart failure is described as the heart's inability to pump enough blood for all of the body's needs (see the page on Heart Failure). In coronary heart disease, accumulation of atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries may prevent heart regions from getting adequate circulation, ultimately resulting in cardiac damage and impaired pumping ability. Myocardial infarction may also damage the heart muscle, which could potentially lead to heart failure. Further, the diminished heart’s capacity to pump blood in cases of dilated cardiomyopathy may lead to heart failure. Because physical exercise increases the demand on the weakened heart, measures of exercise tolerance are frequently used to monitor the severity of heart failure. Echocardiography is also used to determine the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), an objective measure of the heart's pumping ability. An LVEF of less than 40% is indicative of systolic heart failure (52).

An abnormal acylcarnitine profile and a high acylcarnitine to free carnitine ratio in the blood of patients with heart failure have been linked to disease severity and poor prognosis (53-55). Addition of L-carnitine to standard medical therapy for heart failure has been evaluated in several clinical trials. A 2013 meta-analysis of 17 randomized, placebo-controlled studies in a total of 1,625 participants with heart failure found that oral L-carnitine (1.5-6 g/day for seven days to three years) significantly improved several measures of cardiac functional capacity (including exercise tolerance and markers of the left ventricle function), yet had no impact on all-cause mortality (56).

Angina pectoris

Angina pectoris is chest pain that occurs when the coronary blood supply is insufficient to meet the metabolic needs of the heart muscle (as with ischemic heart disease; see the page on Angina Pectoris) (57). In a prospective cohort study in over 4,000 participants with suspected angina pectoris, elevated concentrations of certain acylcarnitine intermediates in blood were associated with fatal and non-fatal acute myocardial infarction (58). In early studies, the addition of oral L-carnitine or propionyl-L-carnitine to pharmacologic therapy for chronic stable angina modestly improved exercise tolerance and decreased electrocardiographic signs of ischemia during exercise testing in some angina patients (59-61). Another early study examined hemodynamic and angiographic variables before, during, and after administering intravenous propionyl-L-carnitine (15 mg/kg body weight) in men with myocardial dysfunction and angina pectoris (62). In this study, propionyl-L-carnitine decreased myocardial ischemia, evidenced by significant reductions in ST-segment depression and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (62). No recent and/or large-scale studies have been conducted to further examine the potential benefit of L-carnitine or propionyl-L-carnitine in the management of angina pectoris.

Intermittent claudication in peripheral arterial disease

In peripheral arterial disease, atherosclerosis of the arteries that supply the lower extremities may diminish blood flow to the point that the metabolic needs of exercising muscles are not sufficiently met, thereby leading to ischemic leg or hip pain known as claudication (see the page on Intermittent Claudication in Peripheral Arterial Disease) (63). Several clinical trials have found that treatment with propionyl-L-carnitine improves exercise tolerance in some patients with intermittent claudication. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-titration study, 1 to 3 g/day of oral propionyl-L-carnitine for 24 weeks was well tolerated and improved maximal walking distance in patients with intermittent claudication (64). In a randomized, placebo-controlled study of 495 patients with intermittent claudication, 2 g/day of propionyl-L-carnitine for 12 months significantly increased maximal walking distance and the distance walked prior to the onset of claudication in patients whose initial maximal walking distance was less than 250 meters (m), but no effect was seen in patients who had an initial maximal walking distance greater than 250 m (65). More recent trials have associated oral propionyl-L-carnitine supplementation (2 g/day for several months) with improved walking distance and claudication onset time (66, 67), as well as with higher pain-free walking distance and higher ankle-brachial index (a diagnostic measure of peripheral arterial disease) (68). Two 2013 systematic reviews of interventions concluded that the modest benefit of propionyl-L-carnitine on walking performance was equivalent or superior to that obtained with drugs approved for claudication in the US (e.g., pentoxyphylline, cilostazol) yet inferior to improvements seen with supervised exercise interventions (69, 70).

End-stage renal disease

L-Carnitine and short/medium-chain acylcarnitine molecules are removed from the circulation during hemodialysis. Both L-carnitine loss into the dialysate and impaired synthesis by the kidneys contribute to a progressive carnitine deficiency in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis (71). The low clearance of long-chain acylcarnitine molecules leads to a high acylcarnitine-to-L-carnitine ratio that has been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (72). Carnitine depletion in patients undergoing hemodialysis may lead to various conditions, such as muscle weakness and fatigue, plasma lipid abnormalities, and refractory anemia. A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials in a total of 1,734 patients with ESRD found that L-carnitine treatment — administered either orally or intravenously — resulted in reductions of serum C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation and predictor of mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis) and LDL-cholesterol, although the latter was not deemed to be clinically relevant (73). There was no effect of L-carnitine on other serum lipids (i.e., total and HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides) and anemia-related indicators (i.e., hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, albumin, and required dose of recombinant erythropoietin) (73).

The US National Kidney Foundation did not recommend routine administration of L-carnitine to subjects undergoing dialysis yet encouraged the development of trials in patients with select symptoms that do not respond to standard therapy, i.e., persistent muscle cramps or hypotension during dialysis, severe fatigue, skeletal muscle weakness or myopathy, cardiomyopathy, and anemia requiring large doses of erythropoietin (74, 75).

Finally, the use of L-carnitine (10-20 mg/kg body weight given as a slow bolus injection) is approved by the US FDA to treat L-carnitine deficiency in subjects with ESRD undergoing hemodialysis (76).

Peripheral neuropathy

Antiretroviral-related peripheral neuropathy

The use of certain antiretroviral agents (nucleoside analogs) has been associated with an increased risk of developing peripheral neuropathy in HIV-positive individuals (77, 78). Small, uncontrolled, open-label intervention studies have suggested a beneficial effect of acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) in patients with painful neuropathies. An early uncontrolled study found that 10 out of 16 HIV-positive subjects with painful neuropathy reported improvement after three weeks of intravenous or intramuscular ALCAR treatment (79). Results from another uncontrolled intervention in 21 HIV-positive patients suggested that long-term (two to four years) oral ALCAR supplementation (1.5 g/day) may be a beneficial adjunct to antiretroviral therapy to improve neuropathic symptoms in some HIV-infected individuals (80, 81). Additionally, two small studies in participants presenting with antiretroviral-induced neuropathy found significant reduction in subjects' mean pain intensity with oral ALCAR (1-3 g/day) for 4 to 24 weeks, but no effect on objective neurophysiological parameters was found (82, 83).

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 90 HIV-positive patients with symptomatic distal symmetrical polyneuropathy found no benefit of intramuscular injection with 1 g/day of ALCAR for two weeks in the intention-to-treat analysis, but there was some pain relief in the group of 66 patients who completed the trial (84). Large-scale, controlled studies are needed before any conclusions can be drawn.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy

Peripheral nerve dysfunction occurs in about 50% of people with diabetes mellitus, and chronic neuropathic pain is present in about one-third of people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (85). Advanced stages of diabetic peripheral neuropathy can lead to recurrent foot ulcers and infections, and eventually amputations (86). A 2019 systematic review (87) identified three placebo-controlled interventions that examined the effect of oral supplementation with acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR; 1.5-3.0 g/day for one year) in individuals with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (3, 88). Low-quality evidence suggested a lower level of pain with ALCAR, as measured with a visual scale analog. Low-quality evidence from another trial that compared the effect of ALCAR (1.5 g/day) with that of methylcobalamin (1.5 mg/day) for 24 weeks suggested no difference between treatments regarding the extent of functional disability (using the Neuropathy Disability Scale) or measures of symptom quality and severity (using the Neuropathy Symptom Scale) (89).

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

A few randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have examined whether ALCAR might help prevent or treat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. A trial in 150 participants with either ovarian cancer or castration-resistant prostate cancer found no evidence that ALCAR (1g every 3 days) given with the anticancer drug sagopilone (for up to six cycles of treatment) reduced the overall risk of peripheral neuropathy compared to a placebo (90). However, ALCAR reduced the risk of high-grade sagopilone-induced neuropathy (90). In contrast, another trial in 409 women with breast cancer found that ALCAR (3 g/day for 24 weeks) increased anticancer drug (taxanes)-induced peripheral neuropathy and decreased measures of functional status compared to placebo (91). A follow-up study reported that the negative impact of 24-week treatment with ALCAR was still observed at week 52; however, no differences between ALCAR and placebo were apparent at week 104 (92). Finally, one trial in 239 participants already suffering from chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy reported a reduction in the severity of neuropathic symptoms with ALCAR (3 g/day for eight weeks) compared to placebo (93). Improvements in electrophysiological parameters were also observed with ALCAR treatment (93).

The results from these trials are conflicting and thus difficult to interpret. The efficacy of ALCAR in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy remains to be established (94).

Depression

A 2018 meta-analysis identified 12 randomized controlled trials, including 791 participants, that examined the effect of ALCAR on symptoms of depression (95). Evidence from nine trials suggested a reduction in depressive symptoms with ALCAR (3 g/day for a median 8 weeks) compared to a placebo. Three trials that compared ALCAR treatment (1-3 g/day for 7-12 weeks) and antidepressant medications found ALCAR was as effective as antidepressants in treating depressive symptoms (95). Another meta-analysis of trials that compared the safety profile of antidepressants found evidence of fewer adverse effects, and consequently, better adherence to treatment with ALCAR compared to placebo and in contrast to classical pharmaceutical agents (96).

Alzheimer's disease

The metabolomic profiling of acylcarnitine molecules showed variations in serum concentrations of subjects along the continuum from cognitively healthy to affected by Alzheimer's disease (97). Changes in the blood concentrations of specific acylcarnitines in subjects with either subjective memory complaints, mild cognitive impairment, or Alzheimer's disease, compared to cognitively healthy peers may reflect changes in the transport of fatty acids into the mitochondria and/or impairments in energy production. Several clinical trials conducted in the 1990s examined the effect of acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) treatment on the cognitive performance of patients clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. Early, small trials suggested a beneficial effect of ALCAR with respect to cognitive decline (98-100), whereas later, larger trials found little-to-no effect compared to placebo (101-103). However, a 2003 systematic review highlighted differences in methodologies between early and later studies that make it difficult to compare results (104). Nevertheless, the pooled analysis of 16 trials suggested improvements in the summary measure of patients' global functioning (assessed with the Clinical Global Impressions [CGI-I] scale) after 12 and 24 weeks of (but not after 52 weeks) of ALCAR treatment (1-3 g/day) and in cognitive performance (assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] scale) after 24 weeks (but not at 12 or 52 weeks) (104). A 2003 meta-analysis of 21 trials found that ALCAR was superior to placebo in several psychometric tests assessing global patient functioning, attention, memory, and some intellectual functions (105).

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy refers to the occurrence of a spectrum of neuropsychiatric signs or symptoms in individuals with acute or chronic liver disease (106). Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy may not feature any symptoms beyond abnormal behavior on psychometric tests or symptoms that are nonspecific in nature. In contract, overt hepatic encephalopathy can present with disorientation, obvious personality change, inappropriate behavior, somnolence, stupor, confusion, and coma (106). Changes in mental status are thought to be caused by the liver failing to detoxify neurotoxic compounds like ammonia. A 2019 systematic review of five placebo-controlled trials conducted by one group of investigators examined the effect of acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) in 398 participants with cirrhosis and portal hypertension (high blood pressure in the portal vein) and presenting with either subclinical or overt hepatic encephalopathy. ALCAR was either administered orally (4 g/day for 90 days) in four trials or intravenously (4 g/day for three days) in one trial. ALCAR was found to significantly reduce blood ammonium concentration compared to placebo. However, none of the trials reported on serious adverse outcomes, including mortality. Additionally, the evidence was too limited to assess the impact on quality of life or mental and physical fatigue.

Cancer-related fatigue

Fatigue is not uncommon in people who have undergone chemotherapy and survived cancer, with fatigue symptoms depending on the specific type of cancer and treatment. Cancer-related fatigue can persist well beyond the end of chemotherapy and be associated with cognitive and functional decline, insomnia, depression, and a reduction in the quality of life (107). A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis identified 12 intervention studies that assessed the effect of L-carnitine or ALCAR on cancer-related fatigue (reported as a primary or secondary outcome) in cancer survivors (108). Three studies had no control arm, eight studies were open-label, and eight studies included fewer than 100 participants. Overall, only three studies were deemed of good quality. The meta-analysis of these three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials found no effect of L-carnitine (0.25-4 g/day for 1 week to 3 months) or ALCAR (3 g/day for 6 months) on the level of cancer-related fatigue (108).

Infertility

L-Carnitine is concentrated in the epididymis, where sperm mature and acquire their motility (109). An early cross-sectional study of 101 fertile and infertile men found that L-carnitine concentrations in semen were positively correlated with the number of sperm, the percentage of motile sperm, and the percentage of normal appearing sperm in the sample (110), suggesting that L-carnitine may play an important role in male fertility. One placebo-controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial in 86 subjects with fertility issues found that supplementation with L-carnitine (2 g/day) for two months improved sperm quality, as evidenced by increases in sperm concentration and motility (111). In another placebo-controlled trial conducted by the same group, similar improvements in sperm motility were observed in participants supplemented with 2g/day of L-carnitine and 1 g/day of acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) for six months (112). In both trials, the effect of carnitine was greater in the most severe cases of asthenozoospermia (reduced sperm motility) at baseline (111, 112). Another placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study in 44 men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia found an increase in sperm motility in those given ALCAR alone (3 g/day) or ALCAR (1 g/day) plus L-carnitine (2 g/day) compared to those given L-carnitine alone (2 g/day) or a placebo (113). However, a pooled analysis of the two trials that employed ALCAR found no significant effect of ALCAR and L-carnitine on sperm concentration, motility, and morphology (114). Evidence from larger scale clinical trials is still needed to determine whether L-carnitine and ALCAR could play a role in the treatment of male infertility.

Physical health

Frailty

Frailty is a syndrome prevalent among geriatric populations and characterized by a functional decline and a loss of independence to perform the activities of daily living. Frailty in individuals may include at least three of the following symptoms: unintentional weight loss, exhaustion (poor endurance), weakness (low grip strength), slowness, and physical inactivity (115). It is believed that early stages of frailty are amenable to interventions that could avert adverse outcomes, including the increased risk of hospitalization and premature death (116). The suggestion that carnitine deficiency may lead to frailty through mitochondrial dysfunction (117) has been examined in one trial. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 58 older adults identified as "pre-frail" found an decrease in a Frailty Index score and an improvement in the hand grip test in individuals supplemented with L-carnitine (1.5 g/day) over 10 weeks but not in those given a placebo (118). However, there was no difference in Frailty Index and hand grip test scores between supplemental L-carnitine and placebo groups.

Skeletal muscle wasting

Loss of skeletal muscle mass is associated with a decrease in muscle strength and occurs with aging (119), as well as in several pathological conditions (120-122). Based on preclinical studies, it has been suggested that L-carnitine supplementation could limit the imbalance between protein anabolism (synthesis) and catabolism (degradation) that leads to skeletal muscle wasting (42). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 28 older women (ages, 65-70 years) found no effect of L-carnitine supplementation (1.5 g/day for 24 weeks) on serum pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations, body mass and composition (lean [fat-free] mass and skeletal muscle mass), or measures of skeletal muscle strength (123). In contrast, a retrospective cohort study in patients with cirrhosis found a reduced rate of skeletal muscle loss over at least six months in those who were administered L-carnitine (N=35; mean dose, 1.02 g/day) compared to those who were not (124). Of note, supplementation with L-carnitine was given in patients with cirrhosis to control hyperammonemia (N=27), to reduce muscle cramps (N=6), or to prevent carnitine deficiency (N=2). One major limitation of this study beyond its retrospective design is that patients who received L-carnitine had a significantly different clinical presentation; in particular, liver dysfunction was significantly more severe in these patients than in those who were not supplemented (124).

Muscle cramps

Muscle cramps are involuntary and painful contractions of skeletal muscles. Two uncontrolled studies conducted in participants with cirrhosis found that L-carnitine supplementation was safe to use at doses of 0.9 to 1.2 g/day for eight weeks (125) and 1 g/day for 24 weeks (126) and might be considered to control the frequency of cramps. However, whether supplemental L-carnitine can be efficacious to limit the incidence of muscle cramps in patients with cirrhosis remains unknown. An open-label, non-randomized trial in 69 patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus found a reduction in the incidence of muscle cramps and an improvement in the quality of life of those prescribed 0.6 g/day of L-carnitine for four months compared to controls (127). In contrast, there is little evidence to date to suggest that supplemental L-carnitine could reduce muscle cramps in patients undergoing hemodialysis (128). Well-designed trials are necessary to examine whether L-carnitine could be helpful in the management of cramps.

Physical performance

Interest in the potential of L-carnitine supplementation to improve athletic performance is related to its important roles in energy metabolism. A number of small, poorly controlled studies have reported that either acute (dose given one hour before exercise bout) or short-term (two to three weeks) supplementation with L-carnitine (2 to 4 g/day) supported energy production, cardiorespiratory fitness, and endurance capacity during physical exercise (reviewed in 129). However, in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 32 healthy adults, propionyl-L-carnitine (1 g/day or 3 g/day) for eight weeks did not improve aerobic or anaerobic exercise performance (130). An intervention study compared the effect of L-carnitine supplementation (2 g/day for 12 weeks) on plasma and skeletal muscle carnitine concentrations and physical performance between 16 vegetarian and 8 omnivorous male participants (131). At baseline, plasma carnitine concentration was about 10% lower in vegetarian compared to omnivorous participants. However, the content carnitine in skeletal muscle, phosphocreatine, ATP, glycogen, and lactate, as well as measures of physical performance during exercise were equivalent between vegetarians and omnivores. While L-carnitine supplementation normalized plasma carnitine concentration in vegetarians to that observed in omnivores, there was no effect on energy metabolism and physical performance compared to no supplementation and between vegetarians and omnivores (131).

Sources

Biosynthesis

The normal rate of L-carnitine biosynthesis in humans ranges from 0.16 to 0.48 mg/kg of body weight/day (4). Thus, a 70 kg (154 1b) person would synthesize between 11 and 34 mg of carnitine per day. This rate of synthesis, combined with efficient (95%) L-carnitine reabsorption by the kidneys, is sufficient to prevent deficiency in generally healthy people, including strict vegetarians (132).

Food sources

Meat, poultry, fish, and dairy products are the richest sources of L-carnitine, while fruit, vegetables, and grains contain relatively little L-carnitine. Omnivorous diets have been found to provide 23 to 135 mg/day of L-carnitine for an average 70 kg person, while strict vegetarian diets may provide as little as 1 mg/day for a 70 kg person (8). Between 54% and 86% of L-carnitine from food is absorbed, compared to 5%-25% from oral supplements (0.6-7 g/day) (13). Non-milk-based infant formulas (e.g., soy formulas) should be fortified so that they contain 11 mg/L of L-carnitine. Some carnitine-rich foods and their carnitine content in milligrams (mg) are listed in Table 1.

Supplements

Intravenous L-carnitine

Intravenous L-carnitine is available by prescription only for the treatment of primary and secondary L-carnitine deficiencies (76).

Oral L-carnitine

Oral L-carnitine is available by prescription for the treatment of primary and secondary L-carnitine deficiencies (76). It is also available without a prescription as a nutritional supplement; supplemental doses usually range from 0.5 to 2 g/day.

Acetyl-L-carnitine

Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) is available without a prescription as a nutritional supplement. In addition to providing L-carnitine, it provides acetyl groups that may be used in the formation of the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. Supplemental doses usually range from 0.5 to 2 g/day (133).

Propionyl-L-carnitine

Propionyl-L-carnitine is not approved by the US FDA for use as a drug to prevent or treat any condition. It is, however, available without prescription as a nutritional supplement.

See Figure 1 for the chemical structures of L-carnitine, acetyl-L-carnitine, and propionyl-L-carnitine.

Safety

Adverse effects

In general, L-carnitine appears to be well tolerated; no toxic effects have been reported in relation to intakes of high doses of L-carnitine. L-Carnitine supplementation may cause mild gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. Supplements providing more than 3 g/day may cause a "fishy" body odor. Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) has been reported to increase agitation in some Alzheimer's disease patients (133). Despite claims that L-carnitine or ALCAR might increase seizures in some individuals with seizure disorders (133), these are not supported by any scientific evidence (134). Only the L-isomer of carnitine is biologically active; the D-isomer may actually compete with L-carnitine for absorption and transport, thereby increasing the risk of L-carnitine deficiency (4). Supplements containing a mixture of the D- and L-isomers (D,L-carnitine) have been associated with muscle weakness in patients with kidney disease. Long-term studies examining the safety of ALCAR supplementation in pregnant and breast-feeding women are lacking (133).

Drug interactions

Pivalic acid combines with L-carnitine and is excreted in the urine as pivaloylcarnitine, thereby increasing L-carnitine losses (see also Secondary carnitine deficiency). Consequently, prolonged use of pivalic acid-containing antibiotics, including pivampicillin, pivmecillinam, pivcephalexin, and cefditoren pivoxil (Spectracef), can lead to secondary L-carnitine deficiency (135). The anticonvulsant valproic acid (Depakene) interferes with L-carnitine biosynthesis in the liver and forms with L-carnitine a valproylcarnitine ester that is excreted in the urine. However, L-carnitine supplements are necessary only in a subset of patients taking valproic acid. Risk factors for L-carnitine deficiency with valproic acid include young age (<2 years), severe neurological problems, use of multiple antiepileptic drugs, poor nutrition, and consumption of a ketogenic diet (135). There is insufficient evidence to suggest that nucleoside analogs used in the treatment of HIV infection (i.e., zidovudine [AZT], didanosine [ddI], zalcitabine [ddC], and stavudine [d4T] or certain cancer chemotherapy agents (i.e., ifosfamide, cisplatin) increase the risk of secondary L-carnitine deficiency (135).

Authors and Reviewers

Originally written in 2002 by:

Jane Higdon, Ph.D.

Linus Pauling Institute

Oregon State University

Updated in April 2007 by:

Victoria J. Drake, Ph.D.

Linus Pauling Institute

Oregon State University

Updated in April 2012 by:

Victoria J. Drake, Ph.D.

Linus Pauling Institute

Oregon State University

Updated in July 2019 by:

Barbara Delage, Ph.D.

Linus Pauling Institute

Oregon State University

Reviewed in December 2019 by:

Tory M. Hagen, Ph.D.

Principal Investigator, Linus Pauling Institute

Professor, Dept. of Biochemistry and Biophysics

Helen P. Rumbel Professor for Healthy Aging Research

Oregon State University

Copyright 2002-2024 Linus Pauling Institute

References

1. Rebouche CJ. Carnitine. In: Shils ME, Shike M, Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2006:537-544.

2. Fraenkel G, Friedman S. Carnitine. Vitam Horm. 1957;15:73-118. (PubMed)

3. De Grandis D, Minardi C. Acetyl-L-carnitine (levacecarnine) in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy. A long-term, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Drugs R D. 2002;3(4):223-231. (PubMed)

4. Seim H, Eichler K, Kleber H. L(-)-Carnitine and its precursor, gamma-butyrobetaine. In: Kramer K, Hoppe P, Packer L, eds. Nutraceuticals in Health and Disease Prevention. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2001:217-256.

5. Rebouche CJ. Kinetics, pharmacokinetics, and regulation of L-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1033:30-41. (PubMed)

6. Rebouche CJ. Carnitine. In: Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL, Ziegler TR, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 11th ed. Baltimore; 2014:440-446.

7. Rebouche CJ. Ascorbic acid and carnitine biosynthesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(6 Suppl):1147S-1152S. (PubMed)

8. Evans AM, Fornasini G. Pharmacokinetics of L-carnitine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(11):941-967. (PubMed)

9. Lombard KA, Olson AL, Nelson SE, Rebouche CJ. Carnitine status of lactoovovegetarians and strict vegetarian adults and children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50(2):301-306. (PubMed)

10. Rebouche CJ, Chenard CA. Metabolic fate of dietary carnitine in human adults: identification and quantification of urinary and fecal metabolites. J Nutr. 1991;121(4):539-546. (PubMed)

11. Gross CJ, Henderson LM, Savaiano DA. Uptake of L-carnitine, D-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine by isolated guinea-pig enterocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;886(3):425-433. (PubMed)

12. Rebouche CJ, Lombard KA, Chenard CA. Renal adaptation to dietary carnitine in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58(5):660-665. (PubMed)

13. Rebouche CJ. L-carnitine. In: Erdman JWJ, Macdonald IA, Zeisel SH, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 10th ed. ILSI/Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:391-404.

14. McGrane MM. Carbohydrate metabolism--synthesis and oxidation. In: Stipanuk MH, ed. Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Human Nutrition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 2000:158-210.

15. Solarska K, Lewinska A, Karowicz-Bilinska A, Bartosz G. The antioxidant properties of carnitine in vitro. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2010;15(1):90-97. (PubMed)

16. Costell M, O'Connor JE, Grisolia S. Age-dependent decrease of carnitine content in muscle of mice and humans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161(3):1135-1143. (PubMed)

17. Karlic H, Lohninger A, Laschan C, et al. Downregulation of carnitine acyltransferases and organic cation transporter OCTN2 in mononuclear cells in healthy elderly and patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Mol Med (Berl). 2003;81(7):435-442. (PubMed)

18. Hagen TM, Ingersoll RT, Wehr CM, et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine fed to old rats partially restores mitochondrial function and ambulatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(16):9562-9566. (PubMed)

19. Pesce V, Fracasso F, Cassano P, Lezza AM, Cantatore P, Gadaleta MN. Acetyl-L-carnitine supplementation to old rats partially reverts the age-related mitochondrial decay of soleus muscle by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13(2-3):148-151. (PubMed)

20. Gomez LA, Heath SH, Hagen TM. Acetyl-l-carnitine supplementation reverses the age-related decline in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) activity in interfibrillar mitochondria without changing the l-carnitine content in the rat heart. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133(2-3):99-106. (PubMed)

21. Muthuswamy AD, Vedagiri K, Ganesan M, Chinnakannu P. Oxidative stress-mediated macromolecular damage and dwindle in antioxidant status in aged rat brain regions: role of L-carnitine and DL-alpha-lipoic acid. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;368(1-2):84-92. (PubMed)

22. Kumaran S, Panneerselvam KS, Shila S, Sivarajan K, Panneerselvam C. Age-associated deficit of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle: role of carnitine and lipoic acid. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;280(1-2):83-89. (PubMed)

23. Kumaran S, Subathra M, Balu M, Panneerselvam C. Supplementation of L-carnitine improves mitochondrial enzymes in heart and skeletal muscle of aged rats. Exp Aging Res. 2005;31(1):55-67. (PubMed)

24. Savitha S, Panneerselvam C. Mitochondrial membrane damage during aging process in rat heart: potential efficacy of L-carnitine and DL alpha lipoic acid. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127(4):349-355. (PubMed)

25. Savitha S, Sivarajan K, Haripriya D, Kokilavani V, Panneerselvam C. Efficacy of levo carnitine and alpha lipoic acid in ameliorating the decline in mitochondrial enzymes during aging. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(5):794-800. (PubMed)

26. Sethumadhavan S, Chinnakannu P. Carnitine and lipoic Acid alleviates protein oxidation in heart mitochondria during aging process. Biogerontology. 2006;7(2):101-109. (PubMed)

27. Sundaram K, Panneerselvam KS. Oxidative stress and DNA single strand breaks in skeletal muscle of aged rats: role of carnitine and lipoicacid. Biogerontology. 2006;7(2):111-118. (PubMed)

28. Sethumadhavan S, Chinnakannu P. L-carnitine and alpha-lipoic acid improve age-associated decline in mitochondrial respiratory chain activity of rat heart muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(7):650-659. (PubMed)

29. Tamilselvan J, Jayaraman G, Sivarajan K, Panneerselvam C. Age-dependent upregulation of p53 and cytochrome c release and susceptibility to apoptosis in skeletal muscle fiber of aged rats: role of carnitine and lipoic acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(12):1656-1669. (PubMed)

30. Aliev G, Liu J, Shenk JC, et al. Neuronal mitochondrial amelioration by feeding acetyl-L-carnitine and lipoic acid to aged rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(2):320-333. (PubMed)

31. Olson AL, Nelson SE, Rebouche CJ. Low carnitine intake and altered lipid metabolism in infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49(4):624-628. (PubMed)

32. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Soy protein-based formulas: recommendations for use in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1):148-152.

33. Frigeni M, Balakrishnan B, Yin X, et al. Functional and molecular studies in primary carnitine deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(12):1684-1699. (PubMed)

34. Magoulas PL, El-Hattab AW. Systemic primary carnitine deficiency: an overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:68. (PubMed)

35. Knottnerus SJG, Bleeker JC, Wust RCI, et al. Disorders of mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation and the carnitine shuttle. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19(1):93-106. (PubMed)

36. Pons R, De Vivo DC. Primary and secondary carnitine deficiency syndromes. J Child Neurol. 1995;10 Suppl 2:S8-24. (PubMed)

37. Gregory MJ, Schwartz GJ. Diagnosis and treatment of renal tubular disorders. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18(3):317-329. (PubMed)

38. Calvani M, Benatti P, Mancinelli A, et al. Carnitine replacement in end-stage renal disease and hemodialysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1033:52-66. (PubMed)

39. Stanley CA. Carnitine deficiency disorders in children. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1033:42-51. (PubMed)

40. El-Gharbawy A, Vockley J. Inborn errors of metabolism with myopathy: defects of fatty acid oxidation and the carnitine shuttle system. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65(2):317-335. (PubMed)

41. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Vitamin C. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000:95-185. (National Academy Press)

42. Ringseis R, Keller J, Eder K. Mechanisms underlying the anti-wasting effect of L-carnitine supplementation under pathologic conditions: evidence from experimental and clinical studies. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52(5):1421-1442. (PubMed)

43. Xu Y, Jiang W, Chen G, et al. L-carnitine treatment of insulin resistance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26(2):333-338. (PubMed)

44. Vidal-Casariego A, Burgos-Pelaez R, Martinez-Faedo C, et al. Metabolic effects of L-carnitine on type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2013;121(4):234-238. (PubMed)

45. Asadi M, Rahimlou M, Shishehbor F, Mansoori A. The effect of l-carnitine supplementation on lipid profile and glycaemic control in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. (PubMed)

46. Parvanova A, Trillini M, Podesta MA, et al. Blood pressure and metabolic effects of acetyl-l-carnitine in type 2 diabetes: DIABASI randomized controlled trial. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(5):420-436. (PubMed)

47. Davini P, Bigalli A, Lamanna F, Boem A. Controlled study on L-carnitine therapeutic efficacy in post-infarction. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1992;18(8):355-365. (PubMed)

48. Xue YZ, Wang LX, Liu HZ, Qi XW, Wang XH, Ren HZ. L-carnitine as an adjunct therapy to percutaneous coronary intervention for non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21(6):445-448. (PubMed)

49. Iyer R, Gupta A, Khan A, Hiremath S, Lokhandwala Y. Does left ventricular function improve with L-carnitine after acute myocardial infarction? J Postgrad Med. 1999;45(2):38-41. (PubMed)

50. Tarantini G, Scrutinio D, Bruzzi P, Boni L, Rizzon P, Iliceto S. Metabolic treatment with L-carnitine in acute anterior ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. A randomized controlled trial. Cardiology. 2006;106(4):215-223. (PubMed)

51. DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, Menezes AR, O'Keefe JH. L-carnitine in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(6):544-551. (PubMed)

52. Trupp RJ, Abraham WT. Congestive heart failure. In: Rakel RE, Bope ET, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. 54th ed. New York: W.B. Sunders Company; 2002:306-313.

53. Ruiz M, Labarthe F, Fortier A, et al. Circulating acylcarnitine profile in human heart failure: a surrogate of fatty acid metabolic dysregulation in mitochondria and beyond. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313(4):H768-h781. (PubMed)

54. Ueland T, Svardal A, Oie E, et al. Disturbed carnitine regulation in chronic heart failure--increased plasma levels of palmitoyl-carnitine are associated with poor prognosis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):1892-1899. (PubMed)

55. Yoshihisa A, Watanabe S, Yokokawa T, et al. Associations between acylcarnitine to free carnitine ratio and adverse prognosis in heart failure patients with reduced or preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2017;4(3):360-364. (PubMed)

56. Song X, Qu H, Yang Z, Rong J, Cai W, Zhou H. Efficacy and safety of L-carnitine treatment for chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6274854. (PubMed)

57. US Department of Health & Human Services, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Angina. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/angina. Accessed 7/1/19.

58. Strand E, Pedersen ER, Svingen GF, et al. Serum acylcarnitines and risk of cardiovascular death and acute myocardial infarction in patients with stable angina pectoris. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(2). (PubMed)

59. Cacciatore L, Cerio R, Ciarimboli M, et al. The therapeutic effect of L-carnitine in patients with exercise-induced stable angina: a controlled study. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1991;17(4):225-235. (PubMed)

60. Cherchi A, Lai C, Angelino F, et al. Effects of L-carnitine on exercise tolerance in chronic stable angina: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled crossover study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1985;23(10):569-572. (PubMed)

61. Iyer RN, Khan AA, Gupta A, Vajifdar BU, Lokhandwala YY. L-carnitine moderately improves the exercise tolerance in chronic stable angina. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48(11):1050-1052. (PubMed)

62. Bartels GL, Remme WJ, Pillay M, Schonfeld DH, Kruijssen DA. Effects of L-propionylcarnitine on ischemia-induced myocardial dysfunction in men with angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(2):125-130. (PubMed)

63. Mills JL. Peripheral arterial disease. In: Rakel RE, Bope ET, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. 54th ed. New York: W.B. Sunders Company; 2002:340-343.

64. Brevetti G, Perna S, Sabba C, Martone VD, Condorelli M. Propionyl-L-carnitine in intermittent claudication: double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose titration, multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(6):1411-1416. (PubMed)

65. Brevetti G, Diehm C, Lambert D. European multicenter study on propionyl-L-carnitine in intermittent claudication. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(5):1618-1624. (PubMed)

66. Hiatt WR. Carnitine and peripheral arterial disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1033:92-98. (PubMed)

67. Luo T, Li J, Li L, et al. A study on the efficacy and safety assessment of propionyl-L-carnitine tablets in treatment of intermittent claudication. Thromb Res. 2013;132(4):427-432. (PubMed)

68. Santo SS, Sergio N, Luigi DP, et al. Effect of PLC on functional parameters and oxidative profile in type 2 diabetes-associated PAD. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;72(3):231-237. (PubMed)

69. Brass EP, Koster D, Hiatt WR, Amato A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of propionyl-L-carnitine effects on exercise performance in patients with claudication. Vasc Med. 2013;18(1):3-12. (PubMed)

70. Delaney CL, Spark JI, Thomas J, Wong YT, Chan LT, Miller MD. A systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of carnitine supplementation in improving walking performance among individuals with intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229(1):1-9. (PubMed)

71. Hatanaka Y, Higuchi T, Akiya Y, et al. Prevalence of carnitine deficiency and decreased carnitine levels in patients on hemodialysis. Blood Purif. 2019;47 Suppl 2:38-44. (PubMed)

72. Kalim S, Clish CB, Wenger J, et al. A plasma long-chain acylcarnitine predicts cardiovascular mortality in incident dialysis patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000542. (PubMed)

73. Chen Y, Abbate M, Tang L, et al. L-Carnitine supplementation for adults with end-stage kidney disease requiring maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(2):408-422. (PubMed)

74. National Kidney Foundation; Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines for nutrition in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(6 Suppl 2):S1-140. (PubMed)

75. National Kidney Foundation; Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47(5 Suppl 3):S11-145. (PubMed)

76. Natural Medicines. Carnitine: professional handout/administration and dosing. Available at: https://naturalmedicines-therapeuticresearch-com. Accessed 7/1/19.

77. Margolis AM, Heverling H, Pham PA, Stolbach A. A review of the toxicity of HIV medications. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10(1):26-39. (PubMed)

78. Moyle GJ, Sadler M. Peripheral neuropathy with nucleoside antiretrovirals: risk factors, incidence and management. Drug Saf. 1998;19(6):481-494. (PubMed)

79. Scarpini E, Sacilotto G, Baron P, Cusini M, Scarlato G. Effect of acetyl-L-carnitine in the treatment of painful peripheral neuropathies in HIV+ patients. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 1997;2(3):250-252. (PubMed)

80. Hart AM, Wilson AD, Montovani C, et al. Acetyl-l-carnitine: a pathogenesis based treatment for HIV-associated antiretroviral toxic neuropathy. Aids. 2004;18(11):1549-1560. (PubMed)

81. Herzmann C, Johnson MA, Youle M. Long-term effect of acetyl-L-carnitine for antiretroviral toxic neuropathy. HIV Clin Trials. 2005;6(6):344-350. (PubMed)

82. Osio M, Muscia F, Zampini L, et al. Acetyl-l-carnitine in the treatment of painful antiretroviral toxic neuropathy in human immunodeficiency virus patients: an open label study. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11(1):72-76. (PubMed)

83. Valcour V, Yeh TM, Bartt R, et al. Acetyl-l-carnitine and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-associated neuropathy in HIV infection. HIV Med. 2009;10(2):103-110. (PubMed)

84. Youle M, Osio M. A double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre study of acetyl L-carnitine in the symptomatic treatment of antiretroviral toxic neuropathy in patients with HIV-1 infection. HIV Med. 2007;8(4):241-250. (PubMed)

85. Tesfaye S, Selvarajah D. Advances in the epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 Suppl 1:8-14. (PubMed)

86. Dy SM, Bennett WL, Sharma R, et al. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Preventing complications and treating symptoms of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Mar 2017. Report No.: 17-EHC005-EF. (PubMed)

87. Rolim LC, da Silva EM, Flumignan RL, Abreu MM, Dib SA. Acetyl-L-carnitine for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:Cd011265. (PubMed)

88. Sima AA, Calvani M, Mehra M, Amato A. Acetyl-L-carnitine improves pain, nerve regeneration, and vibratory perception in patients with chronic diabetic neuropathy: an analysis of two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):89-94. (PubMed)

89. Li S, Chen X, Li Q, et al. Effects of acetyl-L-carnitine and methylcobalamin for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7(5):777-785. (PubMed)

90. Campone M, Berton-Rigaud D, Joly-Lobbedez F, et al. A double-blind, randomized phase II study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of acetyl-L-carnitine in the prevention of sagopilone-induced peripheral neuropathy. Oncologist. 2013;18(11):1190-1191. (PubMed)

91. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Crew KD, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of acetyl-L-carnitine for the prevention of taxane-induced neuropathy in women undergoing adjuvant breast cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2627-2633. (PubMed)

92. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Crew KD, et al. Two-year trends of taxane-induced neuropathy in women enrolled in a randomized trial of acetyl-L-carnitine (SWOG S0715). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(6):669-676. (PubMed)

93. Sun Y, Shu Y, Liu B, et al. A prospective study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral acetyl-L-carnitine for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(6):4017-4024. (PubMed)

94. van Dam DG, Beijers AJ, Vreugdenhil G. Acetyl-L-carnitine undervalued in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy? Acta Oncol. 2016;55(12):1495-1497. (PubMed)

95. Veronese N, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Ajnakina O, Carvalho AF, Maggi S. Acetyl-L-carnitine supplementation and the treatment of depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2018;80(2):154-159. (PubMed)

96. Meister R, von Wolff A, Mohr H, et al. Comparative safety of pharmacologic treatments for persistent depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153380. (PubMed)

97. Cristofano A, Sapere N, La Marca G, et al. Serum levels of acyl-carnitines along the continuum from normal to Alzheimer's dementia. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155694. (PubMed)

98. Pettegrew JW, Klunk WE, Panchalingam K, Kanfer JN, McClure RJ. Clinical and neurochemical effects of acetyl-L-carnitine in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(1):1-4. (PubMed)

99. Spagnoli A, Lucca U, Menasce G, et al. Long-term acetyl-L-carnitine treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41(11):1726-1732. (PubMed)

100. Sano M, Bell K, Cote L, et al. Double-blind parallel design pilot study of acetyl levocarnitine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(11):1137-1141. (PubMed)

101. Thal LJ, Carta A, Clarke WR, et al. A 1-year multicenter placebo-controlled study of acetyl-L-carnitine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996;47(3):705-711. (PubMed)

102. Thal LJ, Calvani M, Amato A, Carta A. A 1-year controlled trial of acetyl-l-carnitine in early-onset AD. Neurology. 2000;55(6):805-810. (PubMed)

103. Brooks JO, 3rd, Yesavage JA, Carta A, Bravi D. Acetyl L-carnitine slows decline in younger patients with Alzheimer's disease: a reanalysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study using the trilinear approach. Int Psychogeriatr. 1998;10(2):193-203. (PubMed)

104. Hudson S, Tabet N. Acetyl-L-carnitine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003(2):Cd003158. (PubMed)

105. Montgomery SA, Thal LJ, Amrein R. Meta-analysis of double blind randomized controlled clinical trials of acetyl-L-carnitine versus placebo in the treatment of mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(2):61-71. (PubMed)

106. Wijdicks EF. Hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1660-1670. (PubMed)

107. Inglis JE, Lin PJ, Kerns SL, et al. Nutritional interventions for treating cancer-related fatigue: a qualitative review. Nutr Cancer. 2019;71(1):21-40. (PubMed)

108. Marx W, Teleni L, Opie RS, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of carnitine supplementation for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9(11). (PubMed)

109. Jeulin C, Lewin LM. Role of free L-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitine in post-gonadal maturation of mammalian spermatozoa. Hum Reprod Update. 1996;2(2):87-102. (PubMed)

110. Matalliotakis I, Koumantaki Y, Evageliou A, Matalliotakis G, Goumenou A, Koumantakis E. L-carnitine levels in the seminal plasma of fertile and infertile men: correlation with sperm quality. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2000;45(3):236-240. (PubMed)

111. Lenzi A, Lombardo F, Sgro P, et al. Use of carnitine therapy in selected cases of male factor infertility: a double-blind crossover trial. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(2):292-300. (PubMed)

112. Lenzi A, Sgro P, Salacone P, et al. A placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial of the use of combined l-carnitine and l-acetyl-carnitine treatment in men with asthenozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(6):1578-1584. (PubMed)

113. Balercia G, Regoli F, Armeni T, Koverech A, Mantero F, Boscaro M. Placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial on the use of L-carnitine, L-acetylcarnitine, or combined L-carnitine and L-acetylcarnitine in men with idiopathic asthenozoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(3):662-671. (PubMed)

114. Buhling K, Schumacher A, Eulenburg CZ, Laakmann E. Influence of oral vitamin and mineral supplementation on male infertility: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(2):269-279. (PubMed)

115. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255-263. (PubMed)

116. Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwee D, et al. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(12):1163.e1161-1163.e1117. (PubMed)

117. Crentsil V. Mechanistic contribution of carnitine deficiency to geriatric frailty. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(3):265-268. (PubMed)

118. Badrasawi M, Shahar S, Zahara AM, Nor Fadilah R, Singh DK. Efficacy of L-carnitine supplementation on frailty status and its biomarkers, nutritional status, and physical and cognitive function among prefrail older adults: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1675-1686. (PubMed)

119. Dhillon RJ, Hasni S. Pathogenesis and management of sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33(1):17-26. (PubMed)

120. Ebadi M, Montano-Loza AJ. Clinical relevance of skeletal muscle abnormalities in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(11):1493-1499. (PubMed)

121. Kim SH, Shin MJ, Shin YB, Kim KU. Sarcopenia associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Bone Metab. 2019;26(2):65-74. (PubMed)

122. Melenovsky V, Hlavata K, Sedivy P, et al. Skeletal muscle abnormalities and iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: An Exercise (31)P Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study of Calf Muscle. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(9):e004800. (PubMed)

123. Sawicka AK, Hartmane D, Lipinska P, Wojtowicz E, Lysiak-Szydlowska W, Olek RA. L-carnitine supplementation in older women. A pilot study on aging skeletal muscle mass and function. Nutrients. 2018;10(2). (PubMed)

124. Ohara M, Ogawa K, Suda G, et al. L-Carnitine suppresses loss of skeletal muscle mass in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2(8):906-918. (PubMed)

125. Nakanishi H, Kurosaki M, Tsuchiya K, et al. L-carnitine reduces muscle cramps in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(8):1540-1543. (PubMed)

126. Hiraoka A, Kiguchi D, Ninomiya T, et al. Can L-carnitine supplementation and exercise improve muscle complications in patients with liver cirrhosis who receive branched-chain amino acid supplementation? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(7):878-884. (PubMed)

127. Imbe A, Tanimoto K, Inaba Y, et al. Effects of L-carnitine supplementation on the quality of life in diabetic patients with muscle cramps. Endocr J. 2018;65(5):521-526. (PubMed)

128. Lynch KE, Feldman HI, Berlin JA, Flory J, Rowan CG, Brunelli SM. Effects of L-carnitine on dialysis-related hypotension and muscle cramps: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(5):962-971. (PubMed)

129. Fielding R, Riede L, Lugo JP, Bellamine A. L-carnitine supplementation in recovery after exercise. Nutrients. 2018;10(3). (PubMed)

130. Smith WA, Fry AC, Tschume LC, Bloomer RJ. Effect of glycine propionyl-L-carnitine on aerobic and anaerobic exercise performance. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2008;18(1):19-36. (PubMed)

131. Novakova K, Kummer O, Bouitbir J, et al. Effect of L-carnitine supplementation on the body carnitine pool, skeletal muscle energy metabolism and physical performance in male vegetarians. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(1):207-217. (PubMed)

132. Rebouche CJ. Carnitine. In: Shils ME, Olson JA, Shike M, Ross AC, eds. Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:505-512.

133. Hendler SS, Rorvik DR. Acetyl-L-carnitine. PDR for Nutritional Supplements. 2nd ed. Montvale: Thomson Reuters; 2008:13-16.

134. Zeiler FA, Sader N, Gillman LM, West M. Levocarnitine induced seizures in patients on valproic acid: A negative systematic review. Seizure. 2016;36:36-39. (PubMed)

135. Natural Medicines. Carnitine: professional handout/drug interactions. Available at: https://naturalmedicines-therapeuticresearch-com. Accessed 7/1/19.

Coenzyme Q10

Contents

Summary

- Coenzyme Q10 is a fat-soluble compound that is synthesized by the body and can be obtained from the diet. (More information)

- Coenzyme Q10 plays a central role in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). It also functions as an antioxidant in cell membranes and lipoproteins. (More information)

- Endogenous synthesis and dietary intake provide sufficient coenzyme Q10 to prevent deficiency in healthy people, although coenzyme Q10 concentrations in tissues decline with age. (More information)